Two weeks ago I published Squat Rocking 10: Chris Liberator in the 90’s, a tribute mix to original London acid techno hero Chris Liberator. In the blog post I mentioned that I had contacted Chris for an interview but hadn’t heard back. A few days after publishing Chris got in touch and asked if I still wanted to do the interview. Of course! So last Monday I called him up, hit record (thanks Otter.ai!) and we had a nice chat about the early days of the Liberator crew, the birth of Stay Up Forever, how the London squat party scene developed through the 90’s, the genesis of the acid techno sound and much much more. Obviously it’s edited for clarity but I’ve tried to keep the editing pretty minimal, so that you can really hear Chris’ voice clearly.

It was a very interesting discussion!

Enjoy the full transcript below … I suggest reading it while listening to the mix. 😉

Pearsall

So because I have such a big record collection, sometimes I try to make a theme to make it easier to make decisions about what to use and whatnot, so the mix only features your tracks up to 99. So, the 90s, I made it a thing because that’s when I started. I’m American, as you can tell, but I was in London as a teenager with my family and so the first squat party I went to was probably in like June 98 in Kennington and I was 17. After that, the next few years I was going to them with friends and stuff, so the usual story. The first one I got dragged to by some older brothers, and I was more into drum n’ bass at the time, but then I went to this, and was like, “Wow, this is crazy!” But to tie in with the theme of the mix, maybe we talk more about the 90s, and the early days of the scene.

Chris Liberator

Do you remember the rigs and stuff that you actually went to?

Pearsall

Yeah! I played for a few rigs as well. I played for Undertow a few times. I played for Pendulum, I played for Stinky Pink. Yeah, and there was like one or two others that I played for whose names I don’t even remember. I didn’t play a huge number of squat party sets but I played for a few when I was like 18/19. I remember once I played for Pendulum, it was in Canning Town by a railroad track, and I came on after D.A.V.E. the Drummer at about 7am or something. And it was in some kind of railway arches and it was funny because the trains were going by, I think maybe a DLR train or something, and you can see these people like fucking looking out the window of the train and being like, “Holy shit! What is going on there?!?”

Chris Liberator

Hahaha … I tell you what, the things we’ve done … You know, because of lockdown, I’ve not been going out. But this week I had a flight to play in Ireland. And it was for a festival that got cancelled, and the flights still stood, they wouldn’t give us the money back. So my friends do free parties over there, literally they’ve been doing them every week and they said “We’ll get Chris over!” So I went to do a free party, and it was just nuts! It was just like the old days, but it wasn’t in a warehouse, it was outside Dublin, in the mountains, in the Wicklow hills. But it was fucking nuts. They just broke into the Forestry Commission, they cut the gate with an angle grinder, then drove up in this van with a generator and a rig in it. We drove it up this mountain track; honestly I was just like this is insane, it was going up these tracks crashing through the undergrowth. We got to the top of this mountain and there was about 50 people out there all like “Waheeeeey!” at three in the morning. It was nuts, I played for five hours. Squat parties here are still going on but due to the lockdown it’s all a bit tough right now.

Pearsall

I kind of stopped going after a few years. I moved up to Scotland and then after that I moved back to America for a few years, so I just stopped going regularly in about 2001 or so, and anyways it was also getting a little sketchy – I remember one of the last ones I went to was in Hackney and there were a lot of crack dealers and I was thinking, you know what, this is not my thing any more.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/A-11716-1083265204.jpg.jpg)

Chris Liberator

Yeah, it always went up and down and it’s quite interesting, when you look at it retrospectively, you go back and look at the eras and I divide it up into the main sound systems that were operating during those times.

So, when it first started for us in 1990/91, we started playing, doing our own things and then we met a lot of rigs very quickly, because everyone’s having the same idea from our scene, the sort of ex-punks and travelers and people like that. So obviously the Spirals (Spiral Tribe), we played with Bedlam every week, and there was like Zero Gravity and this other lot like Verge, Shape and Adrenalin and people like Circus Irritant, Circus Warp, but there’s quite a lot of other people involved. But by the time it gets to 92 and they did Castlemorton, there was all that first wave of rigs, and everybody was there at that festival. And that was really when it kicked off into the Criminal Justice Bill, but those soundsystems were the ones we played on most of the time, and then it kind of changed – Immersion came along, and we were really hooked up to them, so Immersion and Virus and Jibba, they were like the second wave, they were from about 93 to 97/98. And then it changed again and it was like the new wave of rigs like Underground Sounds.

Pearsall

Yeah, I went to a lot of their parties.

Chris Liberator

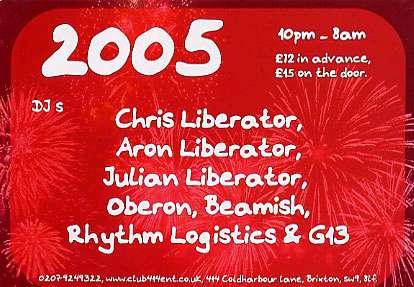

Yeah, I was gonna say that would have been the era when you were going out. Yeah, but the funny thing was that actually went on flourish, I mean after you left. There was a period of time where it did get a bit sketchy but it kind of got its mojo back again and what happened was that when it got to the point, sort of early 2000s to around 2005 when there was a lot of trouble at some of the parties, that kind of thing that you said about little gangs picking up on the parties and coming and starting robbing people, selling the wrong drugs and just doing not nice stuff, you know; to outlaw that a bit the acid techno rigs started to put on parties on Sunday night. I mean it sounds stupid, but they would have a party on Saturday, a lot of drum n’ bass and not that drum n’ bass is sketchy but …

Pearsall

We know it can attract those people!

Chris Liberator

It definitely would attract the local troublemakers. So they would run all the rigs in the night and the acid techno rigs would literally start up in the afternoon on Sunday. It got to the point, because me and D.A.V.E. The Drummer and a lot of the other DJs were traveling anyway to other places we would all arrive on Sunday afternoon, getting back from wherever we’ve been. And it became like Sunday evening was the new Saturday night. And of course, it would always end up running through Monday, the people who were supposed to go to work would end up flaking out. But you know ‘One Night in Hackney‘, that was written about that, people just going out and not coming back until Monday night, but it stopped a lot of the trouble because a lot of people that would come on Saturday night would disappear. So it was a lot friendlier and nicer on the Sunday.

So there was a second wave of sketchiness around 2012/13, that’s when it kind of got a little bit more bad again. That wave passed as well and it was quite good up until lockdown. It’s been a lot of smaller parties, not as regular as they used to be and not as many people but there’s a lovely new wave of young kids as well playing trance and all sorts of stuff coming through and so it hasn’t died. There’s been a lot of publicity about it recently as well, due to lockdown. But the acid techno rigs that are left, the new ones, a lot of them are outside London, but there’s still a few London ones doing stuff – I’ve still played a few parties last year, so it goes on.

Pearsall

I had a question which you kind of touched on already, and it’s that I know some of the history of the scene, and I’ve been listening to this music now for more than 20 years. But I know that you and some of the other guys were involved in the punk scene beforehand. So how did that transition happen to going into techno, like was it just from from going to parties? And then did you start DJing first or making music first? How did that process work?

Chris Liberator

Sure. The first one is music. Literally as musicians because we are all slightly different ages, but most of the people in the crew that made the majority of the music, were actually in bands, so the Geezer, D.A.V.E. the Drummer, myself. Not Julian and Aaron, but I’m trying to think who else …

Pearsall

Was Laurie Immersion in a band?

Chris Liberator

Lawrie was, yeah, Lawrie was in a band. We all came from band backgrounds, that original crew. We all kind of found each other over a period of three or four years, you know the ones you look at the Routemasters and the SUFs and you go right that’s the people that made most of the records. Pretty much every single one of them was in a band before, they came from that scene.

So musically, we’d all come from different types of bands, but all linked with a style of punk or rock that was kind of alternative, in the sense that we all inhabited the squat party scene. So we were all musicians and had all done all kinds of other music as well so that was pretty par for the course. Later on people you had people like Darc Marc that were coming from metal and stuff but again, they all had a musical background so it’s quite interesting that they chose acid techno or they got into the acid techno thing.

I was doing squat parties and stuff with bands and doing a lot of punk stuff – quite political anarcho stuff. And then I kind of got disillusioned with that in the late 80s and my band changed, and I’ve got into another band which was definitely more commercial, but that didn’t really work out, and I kind of got disillusioned with that altogether and started listening to more electronic music, but I had been listening to that all through the punk thing because what people forget about punk was that it’s not just “woi oi!”.

From 1977 to 1982, what came out of punk was a lot of different music. Some of the earliest electronica was defined as punk and new wave, so for me, I followed bands like Cabaret Voltaire and also sort of left field, early electronic pioneers, like the early Kraftwerk records and so that’s always been a part of my history anyway. Electronica was there in that early DIY thing, like Daniel who started Mute Records which was a label that went on to do Depeche Mode and people like that. His first record was like a punk record – he came out with an electronic record but it came through the independent punk network.

Pearsall

Wasn’t NovaMute their sub label?

Chris Liberator

Yeah, later on NovaMute was a sublabel. So he’s even got that connection if you look back from new wave to going on to do techno as well.

So, it was never that far apart from the punk thing, so if you look at my record collection from 1980, there’s tonnes of the earliest Human League records, and when I say earliest Human League they’re not the ones that went on to be famous and commercial, it was pretty electronic and they were on a label called Fast Records which did all sorts of stuff, electronic and punky sort of things, so that connection was there.

So when I got disillusioned with guitar music, I was looking at a lot of new beat stuff and going to see reggae and then from the reggae, people like Adrian Sherwood, doing things like Tackhead in the late 80s which was a kind of heavy dub, electronic with musicians as well, a kind of hybrid thing and again it’s danceable. So there was all that stuff going on, and that was kind of pushing me towards techno anyway. So there’s that side of it.

D.A.V.E. the Drummer was in another band called Back to the Planet, him and Guy were in that, and I didn’t know them then. But they were experimenting with danceable stuff, and I remember in my band we had a sampler and things like that. So when the band finished we were pretty much going down the route of making electronic music.

And then there’s a second aspect to it which is the era where we all came from, which was that we were all sort of squatters, travelers; part of a movement of people that came out of punk into the traveling movement. Anyway so when the actual parties started, in our scene, it wasn’t the original acid house wave in ’88, where the first warehouse parties started. That was never anything to do us, it came from us going out and getting into electronic rave stuff and thinking, “you know what, this isn’t really on our scene, we want to go to squats and places a little bit more dirty”, because that was our background, that’s where we came from.

Pearsall

My understanding is that the original squat party scene was often bands, and then the electronic aspect came into it later.

Chris Liberator

Yeah we all kind of decided in a similar fashion that what we really wanted was to do raves for that kind of scene, and that’s why we started doing our own squat parties and illegal raves. The first Liberator party had bands in a house; a massive house. We drilled holes in the floor and you could go down to the bottom using a pole in the ground. So there was punk bands playing on the bottom, and on the middle floor techno. And then there was a big garden with other stuff going on; all this sort of wild festival type things. It was all part of our culture so we wanted to introduce it to the raves we were doing because that was very much an important part of our background and the whole thing with Spiral Tribe and all the original crews – Bedlam and Zero Gravity and all the other people that we played – it was a movement, we wanted this for our kind of people, not for what was becoming something very commercial, the beginning of clubland.

So that’s the two aspects, the music and the background that we all came from.

Pearsall

So were you going at all to the big early 90s hardcore raves as well?

Chris Liberator

Oh yeah we were doing that as well. We were living in Hackney so we would go to the heavy sort of early drum n’ bass raves like Rat Pack and people like that.

Pearsall

Like Labyrinth and stuff like that.

Chris Liberator

Yes, I mean yeah we were going to that kind of stuff. Labyrinth we used to go to quite a few times and it was very much like going out to any rave, you know, we were happy to go anywhere, take drugs and just get into it. We went down to Hastings Pier, there were big raves on there and these were commercial ones, you know, it didn’t really matter as we’ve enjoyed them all but it didn’t feel like it’s part of our scene.

Pearsall

Was acid always the thing from the beginning or did you kind of gravitate towards that? I mean cuz I was also into punk and metal when I was probably 14 or so and then being in London I got into jungle but then when I heard the sort of stuff you guys were playing, I think the first thing I got was the first mix album, it instantly made sense to me.

Chris Liberator

Yeah. It basically started like this – when we started as DJs, we were buying loads and loads of music, and back then in 1989 / 1990 rave was like you had this nascent techno thing coming from Belgium, you had this Detroit techno, and then you had the early what we would call hardcore now, which basically was the early breakbeat stuff, which went on to be drum n’ bass later but it didn’t start like that, it started as 125 BPM, breakbeat, ravey, sort of synth noises and some four to the floor, it was very mixed up. So you had The Hypnotist and people like that in the UK making kind of techno but it would still have breakbeats in it, it was a right old mishmash but what we really liked was the acid stuff, and I’m not talking acid house but the kind of ravey acid stuff, like some of the Detroit stuff, Underground Resistance for example.

Pearsall

Like Djax-Up Beats and stuff like that as well.

Chris Liberator

Yeah the early Djax stuff, yeah, all that kind of stuff. Miss Djax, all that. So we are buying all this stuff – Like A Tim – it’s weird fucking acid stuff. We liked all that, and we liked all the English rave. And as that music progressed, and it really fucking progressed, fast, from 91 to 93, it was quite mad really. You had all this London ragga and jungle and that just got faster and faster and faster. It started off really slow but by 92 it was up to about 140 BPM, and the early records by Production House and people like that – the big rave records that were played in the English raves – that label jumped from 125 to 160 in a matter of 18 months.

It was just like … whoosh!

And that was how drum n’ bass started – from that. But those records, the early ones, the 125 BPM ones, were being played alongside records from Detroit and places like that. Certainly the Belgian hardcore stuff that again was like slow 125 pounding, much more techno. Some of it was acid. But that stuff as well started to take the English sound and it all fused together, so you get an EP by Kevin Saunderson …

Pearsall

Yeah I got some of those ones, the Tronikhouse.

Chris Liberator

Tronikhouse – they were massive rave records, and he obviously got influenced by the UK sound. So it was a real mashup and a lot of different music came out of that first era, and it went on to become separate scenes of different music. We really liked the breakbeat stuff in the early rave but when it got too fast it became like drum n’ bass and it didn’t really fit with the techie stuff. I played a lot of the breakbeat rave records for the first couple of years of DJing but I’m mixing it with techno as well. Julian tended to go for more four to the floor stuff and Aaron, he liked the weird Dutch ravey stuff.

Pearsall

Like the early gabba kind of stuff or more techno?

Chris Liberator

It was slower than that, records like Maximum Peak. But there was like a point in 93 we decided we’re going to put our first record out. And we had a good strong scene in London by then, doing a lot of parties. But we thought we wanted to start a label, we had a lot of the gear left over from my band. So, we’re making stuff, trying to make tracks. And the first Stay Up Forever, if you ever listen to it, find it, it’s quite a mishmash of stuff, it’s got very fast breaks.

Pearsall

Is it the Sinus Iridium one?

Chris Liberator

It’s before that – two records before.

Pearsall

Was it the first A&E Department?

Chris Liberator

No it’s even before that, that was the second one. But the first one is just us lot under the name Hardcore Disco, which was just me, Aaron and Julian and Paul who started the label with u,s and it’s just a mishmash of stuff.

It’s not acid techno by a longshot but the first track on it, you could see where it’s going. But the other tracks were more experimental, we didn’t have a 303, we couldn’t make acid.

We started to get obsessive about the records we were buying, and by 93/94 there was a kind of European acid sound made by a few people, it got faster. It was a bit more trance. We didn’t like the keyboards, we didn’t like the trancey bits, we liked the acid and the fastness of the beat. We liked the Detroit acid, the heavy stuff but we didn’t like the softer, more melodic stuff.

So we’re putting the records into reviews and different record shops, and Choci’s Chewns sent this message out to us, “oh, Choci from Choci’s Chewns really wants you to go to his record shop, he’s selling all this acid trance, he really thinks you lot will like it. He heard that you’ve got it playlisted, and that you buy it from other places but you can’t find it very easy, and he’s got it all there.”

So I remember turning up at Choci’s, and we started doing a lot of work with Choci after that, making a lot of records with him. He was more into the trancey side of it. Trance, we played it but we didn’t really like the cheesy stuff – when it got too keyboardy and melodic we really didn’t like it. So we knew what we wanted to make, we wanted to make this sound, there’s a few people we were into their style – Pergon, Acrid Abeyance, a few of these German artists.

Pearsall

Oh yeah, those guys really made some amazing records.

Chris Liberator

Obviously Hardfloor were also making this kind of sound; some of it was what we wanted to do and we took that as a blueprint, but we really wanted to create our own thing from that and that’s how we got into the acid thing. And the label really took about nine or ten releases for us to nail it, and meanwhile the label was growing but it was only when we got to about nine or ten that suddenly the English free party scene seemed to start buying the Stay Up Forevers and playing them out. I remember going to some Teknival thing in about 96/97, and I remember hearing Stay Up Forever 9 / 10 / 11 being played everywhere, on every rig. And it was at that point where we met Henry – I made a record for the label Bag, and we went to use his studio and that’s how I met Henry.

Pearsall

Was that the Tasha Killa Pussies one?

Chris Liberator

That’s right, that’s on it as well. Yeah, they used quite a lot of different people from the scene to start that label, but they were mainly people who played at Megadog which was a big event that we all played at.

Pearsall

I don’t think I ever went there but some of my friends were regulars.

Chris Liberator

It was a big, big thing and they were doing live bands – that was where Orbital and all those groups kicked off their live careers. We were resident DJs there for quite a while. And so basically I met Henry and he had a much better studio than us, so we started doing a lot of stuff with him, and he just got bang into it, coming out to squat parties. At the same time we did this party in Dalston, we started using this venue and we did a couple of parties and we needed a rig, and we heard about this rig called Kinky Techno, they started doing these parties in Brixton, and someone told us, “Oh Lawrie hires the rig out, you know you could use it for this warehouse thing you want to do.”

So that’s how we I met Lawrie, he said “Come to my studio, I’m squatted down here, we can make some tracks together.” That’s how we started our connection with Laurie and he’s got into what we were doing and we got into what he’s doing.

Suddenly over a period of about a year, it’s gelled, that little group of musicians, the sound of the label, and everything really started to come together. Lawrie was intrigued that we had the label already up to 11, 12, 13 and he was like, “Oh, I’ve met this guy, he guy wants to start a label.”

And that’s Smitten!

We did the first release for that. And so it went on and this little group of people and labels started, he started Routemaster, and we did the Immersion parties with Lawrie as well. It just went from small to a really big thing really quickly.

And that’s how the whole acid techno thing came together because there was a blueprint of what we wanted to do, but we didn’t achieve it properly, until we met all these other people.

Pearsall

I’ve always wondered this, because you guys really as a group developed a very distinct sound. And I always wondered if this was like a conscious effort, or was it a kind of an organic process that just happened?

Chris Liberator

Bit of both, I mean it was a conscious effort on our part, we spent the first 10 releases on Stay Up Forever trying to achieve the kind of sound that we wanted to do.

Pearsall

The thing you had in your head.

Chris Liberator

Yeah, it only came together when we actually met everybody else, not only because we didn’t have the right gear, or the right studios, but we were all playing that kind of music out, so as Liberator we were already known for playing that kind of sound, acid trance as it was called then.

No one played it in England, it was a very much a European thing. So, although we started playing sort of harder techno and whatever rave sort of stuff was in 91 by 93/94 we were definitely known for playing those sounds, we were the only people on the squat party scene playing, and really the only people in London. I remember Billy Nasty saying “oh you are the only guys who buy these records” when he was working at Zoom.

So we were definitely conscious, we were making a severe effort to try and make this kind of sound ourselves and get that going. And we did manage to do it but when we met all the others they were bang into it, they’d come see us DJ and really liked the sound we were doing. Lawrie was wanting to make acid sounding techno and he had already started doing that when we met him, but didn’t have the arrangements and the sound was slightly different to what we were doing. But we all kind of focused on it so hard.

Henry was making Richie Hawtin style acid in his spare time but he didn’t really have a focus. You know he wasn’t a DJ for starters, he wasn’t going out to parties, it was only kind of a hobby. So when he met us, we were really clear about how we wanted to arrange the records and how they should go and how fast they should be.

So we all developed a sound together because once we got into that mode, we were all just working with each other, left, right and centre and it just spurred that whole thing on. And it wasn’t a conscious effort to make it work but it was the fact that we all met each other and we started working together organically.

Pearsall

So it’s a lucky break. I guess one thing that is always kinda interesting, is that it always sounds like there was a distinct influence from trance in the way it’s structured, with this kind of intro, build up, breakdown, yerrrrr!, the go crazy bit, but obviously with the cheese stripped out. Although I probably have a higher cheese tolerance than you, there’s definitely a lot of the the 90s Hard Trance which is pretty irredeemable!

Chris Liberator

It had speed and the pace and of course the breakdown thing became part of the acid techno blueprint and of course that came from those big trance records, those records like Wittenberg, those kinds of records that had the acid and the trance as well.

Pearsall

Exactly. Noom and Time Unlimited and all those kind of labels.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-31673-1208121678.jpeg.jpg)

Chris Liberator

Yes, but again, they were a bit more cheesy and trancey. Time Unlimited, although we did some work with them, it was a bit more cheesy really, so it worked sometimes for us but I’d play one out of every ten of them. And that one I’d really love, but it would probably be a bit too cheesy on the other releases for me to play. But definitely the blueprint from those trance records was transferred over to the acid techno thing, but the acid techno thing developed into a lot more things. It’s gone back to being very much about the 303, these new school kids that make it now they love all that, but as you know for know yourself the labels developed into different directions.

Pearsall

I guess really in the early 2000’s, a lot of changes.

Chris Liberator

Maximum/Minimum and Raw and all the other labels that came after Pounding Grooves. It went back to being much more techno, although that was always part of it. We loved the acid sound but of course it had limitations and we needed to expand the sound a bit more, get inspired so it went a lot more techno for many many years.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/L-2801-1503671200-7696.jpeg.jpg)

Pearsall

Yeah I remember that in the early 2000s, it definitely got to be less acid and more hard techno, like you say. I was living up in Edinburgh, and I mean any way in Edinburgh they were more into the hard techno sound.

Chris Liberator

Sure, sure, definitely the Scottish thing.

Pearsall

So they really really liked this clanking metallic stuff.

Chris Liberator

We always had that element. Cluster ran concurrently to Stay Up Forver, and was probably the second label we did, it started pretty much around the same time as Routemaster and Smitten. Cluster was our way of putting music out that we liked just as much, so like with Hydraulix and Raw and that third generation of labels that started in the acid techno scene, it did go much more techno. But it was great – we could write acid records and techno records and find a home for them all.

Most people liked it all, but it didn’t mean that people couldn’t go down one route or another. It became its own genre in the end because of that, because there was enough music coming out that people could just play and focus on that and didn’t actually have to dip too much into other kinds of music to bolster up their collections. People did; we all got into various types of other techno and trance and all sorts of things, hard house as well, but there was a lot of music coming from London from that scene. Enough to just on its own stand apart and you could pick and choose from it, you could go “I like Hydraulix, I don’t like Pattern Play”.

Pearsall

Definitely, I could go to Kinetec or Dragon Disc, like I’d go out record shopping every weekend and there’d always be something new to check. And a very high quality threshold and a lot of this stuff has held up really nicely as well, which is not something that you can say for a lot of things. So obviously there was a sort of shift in the early 2000s where it went over to being less 303 and more hard techno. I guess you were always doing kind of your own thing from the wider techno world, did this lead to the sort of wider techno world being more interested in what you were doing? Or what kind of relationships did you have with what you could call the ‘purist’ techno world?

Chris Liberator

Really good question this is, because this is something that plagued us right from the beginning. A lot of the techno techno people didn’t accept what we were doing as proper techno, although I played at some of the biggest techno events in the UK like Atomic Jam. Often we’d be a separate room, doing our own thing and other times I’ve been with Jeff Mills and people like that in the main room. So you had some people accepted it as part of the whole community, other people didn’t, like the real techno snobs that kind of ran the techno scene.

I was the techno reviewer for a magazine, so Prime would send me everything and I’d review Downwards and all the stuff from Birmingham and all the UK releases, like Ben Sims. Everybody’s records. So, we felt we had a strong foothold in the techno scene, especially from the 2000s onwards. But in the early 90s as well, all those people came out of the same scene as us, they all played a right mixture of music anyway because techno was a big church. But when our thing became acid techno, it really got sniffed at by these techno people.

And we were doing a lot of techno as well, like Henry and I did this Ha-Lo project, we ran into Colin Dale on a mission going somewhere and he’s going “Oh my god I’ve been playing this record of yours, I never thought it was you guys! It’s 125 BPM, it’s really funky. It’s you?”

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-47100-1268247551.jpeg.jpg)

Pearsall

You had a few things as well on Eukatech and Off The Wall.

Chris Liberator

Yeah, exactly. I had that label with Nick Spice, and that was doing stuff with Christian Vogel and all sorts of techno people as well. So we had a good connection with the techno people, but some of those people accepted us and some of them didn’t. And if you even look at Stay Up Forever, I mean some of the first releases are people like Cristian Varela and Mike Humphries; a lot of those guys had some of their earliest releases approved for our labels, but it was really frowned on by the mainstream techno community, the people that kind of pulled strings didn’t like us. Prime would send us all the records to review, but they really were snobby about what we did.

Pearsall

What do you think was driving this kind of snobbery? I mean, look, I was only like a teenager, but it was very clear that the quote unquote proper techno world was really very male for one thing. You never saw any women at their parties …

Chris Liberator

Yeah, our parties had loads of women! And on the decks as well. Yeah, very much different things.

Well I don’t know what drove it, we never got to the bottom of it, we spent a lot of years trying to come up with it. Henry tried very hard to ingratiate himself into that scene. Me less.

We just used to laugh because we would send in records to review, and it was a joke, they would just be, “This is generic fucking acid techno, really shit and blah blah blah.” And we just laughed and we would keep sending the records and in the end we met the really defensive guy who was doing the reviews, and he did a night up in the Midlands and he actually invited me to play at one of them and he said, “Look, I know we don’t get along but you are part of the techno scene so we want to have you representing what you do.”

So I actually played for him, even though we used to call their music ‘plod’, you know when it got really slow and monotonous; to us it just wasn’t rave music any more.

Pearsall

Is that where the name Plodbuster came from?

Chris Liberator

Yeah, there was another joke one too. We used to do these jokes amongst ourselves, and they used to complain, “oh the guys from the acid techno scene are calling our music plod!”

It was funny, but later on it got more serious, Atomic Jam stopped booking me to play in the main room because some of the people on the crew that were not the people that ran it, because they liked what we did, but they were just like “this is not proper techno, you can’t book Chris anymore, because that doesn’t fit in the ethos of what we do”, which is quite sad really. And a lot of the bigger techno raves wouldn’t book us, like the proper techno things. But we’ve forged good friendships with quite a lot of the people on the scene, but people like Prime were just dicks to be honest with you, they weren’t very nice people, they thought they were better than everybody else.

Where are they now? We’re still here and they’re not. And now I’m quite thankful to say in the last four or five years all that snobbery is gone.

Lawrie did Pounding Grooves and it was like the best joke on all those guys …

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/L-866-1300183154.jpeg.jpg)

Pearsall

Wasn’t that totally anonymous to start? I remember going to Eukatech and the guy behind the counter telling me it was Lawrie but being like “it’s a secret!”

Chris Liberator

Totally anonymous! All the techno guys were guessing.

“Oh, it’s Cari Lekebusch!”

“Oh it’s Adam Beyer!”

Because no one knew who it was, so they all got tricked by us, we did that, and we did quite a few other releases on other labels which never got found out as being by us, and those guys loved them. Eventually the cat got out of the bag and it’s sort of sussed them out a little bit.

So get over it! We’re all in the same scene, we all need to help each other. Later on, like I say it’s those kind of guys who really just disappeared from the scene. I remember playing in New York and playing at a club for Christian Smith’s night, and Tony Surgeon just danced away right through my set. And you know we always got on well with those guys, it was only the people that drove the techno scene that got really snobby about it, the people that were kind of behind the scenes a bit, they were the people who just didn’t want us to be involved.

Pearsall

I guess it’s like a status thing right? Because if you think about it like an artist, you know an artist will appreciate another artist, even if it’s not maybe the thing they love, but I think there’s a level of appreciation but if your contribution to the scene is that you’re just putting on parties or whatever, or you’re bringing coke to the promoter, it’s not an artistic thing in the same way, it can be more of it’s a status thing. It’s not exactly coming from a creative place.

Chris Liberator

You’ll be pleased to know now that the most amazing thing has happened in the last year or two: acid techno’s been welcomed back into the fold, and what’s happened is you’ve got these DJs like Amelie Lens and all these new big famous, uber-famous DJs, have suddenly just kicked the lid off the box of techno and started playing all this old trance, old acid techno, and mixing them up into their sets. And people like Dax J has played a lot of SUF Collective products, loads of things like Hydraulix, Yolk, you know, the more techie end, the Clusters and stuff, and he even played ‘One Night in Hackney’ for his mix on Radio One a few months ago!

I mean, how mad is that?

Those guys have never had that snobbishness, they’re making real techno techno, and techno is getting harder again. And these guys cut their teeth on acid techno, so they have a lot of respect for us. It is so interesting now because the techno world has opened up again, and so, in the last year or two, acid techno’s become part of it again. We’ve had people like Berghain resident DJs playing things like ‘We Are Ravers’ SUF 90, which is not the techie end of it at all! We are constantly sent videos of these famous techno dj’s playing acid techno records, stuff like the Cluster X-Ray we did with Darc Marc recently, that’s become a massive hit on the techno scene.

So it’s become quite interesting times again, suddenly the music’s part of the whole canon. Perc has been bigging us up for the last few years and he’s come to the SUF office and he’s been like, “I love Stay Up Forever, can I have this record and that record?”

I’ve just done some vocals for Manny D’s album, which is coming out on Perc Trax soon. It’s quite astounding. It has been a big shift as the techno scene has opened up again and it’s all kind of become okay again to play all this stuff alongside the techno things, and the scene has become a lot more open so it’s quite interesting again. It’s funny how things change.

Pearsall

Yeah I definitely like a lot of the new techno stuff that’s come out in the last few years, it’s not as quite as fast as your stuff from the 90s but it’s definitely pretty banging. And it’s funny as well because there’s still a lot of the same gatekeepers who are sniffy about it, they’re calling it ‘business techno’ now.

Chris Liberator

I like to call it whatever but those guys are always complaining.

Pearsall

It can’t be Detroit in 92 until the end of time.

Chris Liberator

Right.

And techno’s been so staid as well. It suddenly went minimal and you couldn’t make anything else, I mean those guys that talk about ‘business techno’: every single one of them just followed the party line to make a living, all these DJs like Marco Bailey, and I’m not slagging him off personally, had to go with the flow to keep their careers going, so they’re all making Hard Groove sort of techno, and then suddenly they’ll start making slow minimal stuff and they didn’t do that because they liked it, I’m sure. They did it because they had to.

So those people that say all that stuff, they’re the worst people for making ‘business techno’. We just kept on doing what we do all the way through, we had more heart and soul and guts, and we didn’t sell out.

They all sold out!

And I’m not talking about the more underground people like the Downwards lot, but a lot of the bigger artists, they all sold themselves out to keep their careers going, and I think we didn’t ever do that. I think it’s wrong for them to say that about how the music’s changed again. I understand what people say about say Drumcode, though, because some of the music they’ve put out in the last few years is pretty awful, it’s almost like trance.

But people like Perc are now battling away, they’re doing great stuff, and it’s got really hard again and I can now play Perc records in my sets again. Perc Trax records go really well in the techno end of my sets. And that’s because they’re a bit like some of the great old Tresor records from the 90’s that were hard and gritty.

Pearsall

It’s like 100 million times better than a really soft kick drum with a bouncing ping-pong ball over the top.

Chris Liberator

God, you know, that was just … I’m sorry. Total junk.

Pearsall

It was garbage!

One last question would be to go back to the second wave which is where I came into it. How did it work behind the scenes? Because I never really knew how it worked; I was just frantically dialing into United Systems at 10 o’clock on a Saturday night. And then one of us would get through. And then we would be be meeting up somewhere in London with our A-Zs and then going to a party. But we never really knew how it worked behind the scenes.

Chris Liberator

Basically, there was United Systems which was running for quite a while; that was a kind of coordinated effort to get everybody on the same page, but of course what would happen is there was the United Systems rigs which would function within that little zone of of parties. I mean as you know yourself for several years, from about 91/92 through to probably about 2007/2008 there were pretty much like two or three different parties every weekend within the underground scene network. There’s a point when I lived on an estate in Kings Cross called Techno Towers and we were all squatting in there, this is probably the end of the 90s, I remember just looking out every weekend and seeing all these trucks pull up from different rigs, getting into things. Louise Plus One would be doing one thing, and Zebedee and them lot would be doing something else. There would be these different rigs setting up and going out and not always doing the same parties, but there were rigs that grouped together that had a different sound to other rigs. They would have their own party line. There was times when everyone would just work together and do a really massive building. I guess in that second wave period, Underground Sound often worked with Virus.

Pearsall

Cross Bones and stuff like that.

Chris Liberator

People like Mayhem. There was lots of little rigs and lots of people doing stuff, a lot of people working together, as well as sometimes just doing parties separately. There was a bit of aggieness between them as well, there was definitely a point when there was a lot of parties with the acid techno rigs doing their thing and a lot of the rigs doing other stuff got a bit shirty because their parties were never quite as well attended, because acid techno then was really flying high. And that I think irked a few people because they were trying to do something different and it didn’t always work.

Pearsall

Drum n’ bass, gabba, dub, etc.

Chris Liberator

Yeah, but they still had a good crowd.

You know people always like to have a go at each other, but I think it worked quite well overall. Sometimes you might go to a teknival abroad and I’d play for one of those rigs just to keep the peace a bit, to say we’re all in it together. We would try to keep being fairly good friends, but there was the odd bit of aggro between the rigs. You know, people would go to Immersion, who would work with Lee from Unsound or somebody like that, maybe one lot would get a building and they would do one rig in one room and then the other lot would set up in the other room, and so on, but sometimes they’d jump ship and maybe do their own party in London or somewhere else.

Pearsall

So I think this is the last one. A lot of these questions obviously are driven purely by my own curiosity from having been there and not knowing how things worked behind the scenes, so how was it that that these parties could happen, you know, sometimes in areas with residents around and and not get shut down so quickly? What was the mechanism? I mean I was at parties that did get shut down by the police, but pretty late on, and sometimes they just came to talk to the rigs and then left.

Chris Liberator

This is pretty much how it worked. And you’ve seen the migration out of the centre of London now as properties have become more expensive in lots of places where we used to do parties like City Road.

Pearsall

So I remember going to a lot of squat parties in Bow, you know, and Hackney, Hackney Wick.

Chris Liberator

Yeah in Hackney you can hardly do parties anymore, the Olympics came in and that changed a lot of the landscape; all those places like Carpenters Road were rebuilt.

Pearsall

Like Waterden Road – that was the first set I ever played was playing for Undertow in this big warehouse on Waterden Road.

Chris Liberator

Waterden Road is gone, they paved over it for the Olympics, it’s a park now. But there’s other places that were really scummy where we did a lot of parties ourselves, like City Road and Market Road, all those places in Islington and you can’t do parties there any more. All those warehouses have been converted into flats now.

Pearsall

Just to drag back to the question, how was it that these parties could happen all night and not get shut down by the police?

Chris Liberator

Oh this is the interesting thing, because what happened when the Criminal Justice Bill came in in like 94, basically it was after Castlemorton and the big illegal raves really went off, so they just decided they were gonna put this law into place. We waited with bated breath to see what would happen in London. Now, Spiral Tribe actually left the country, went off to France to start doing stuff there. There’s a lot of people that were talking about leaving and getting out of England. But what actually happened, they really only used it outside London to stop parties, the big big gatherings like festival sort of style, teknival style things which they didn’t want to see happening again after 1992.

Pearsall

Don’t wake up the farmers!

Chris Liberator

They didn’t want to see the festival scene starting again with this illegal scene going on as well. So that really got only used outside London but in London, the first weekend it came in, Jibba did a party and got away with it, which was a watershed moment, nothing happened, hundreds of people, never got shut down.

But what they did used to do was use noise abatement, so up to now if you do anywhere where it gets noise complaint, you will get shut down. And if they don’t shut you down, they will come back and get your rig in the morning, when people have gone. So, that was what really stopped most parties from happening. One time in the mid 90s I remember an Immersion party where Lawrie came by, got my decks, went off to the party, and I said I’ll join you later.

And then it never got off the ground, police were determined to shut it down and they did. And so there were lot of times when we did get shut down, that’s where records like “Hackney Council Bunch of Cunts” come from! But that particular party was in Stoke Newington near residents and they got a bunch of complaints, so it got shut down. Or every so often they would get orders from above, and there’d be a big clamp down. But if it really wasn’t a direct nuisance to anybody then they went ahead. You know squatting laws were also slightly easier to work with back then, they changed again later. You could get in and party and not get evicted.

And like I say the police were generally fairly easy to deal with, they didn’t want to see any problems, they don’t want to get any noise complaints. If you could get away with all those conditions, then they would generally leave you alone, probably because they were undermanned, and they didn’t want a headache. But if they’ve decided to stop they would.

Pearsall

I definitely would see the police at parties, sometimes at the entrance just talking, maybe once or twice shutting things down, but generally pretty chill and not hostile.

Chris Liberator

Most of the time they were fine, but occasionally they weren’t and they would come in hard. But generally there was a reason for that, there would be something going on with the party that hadn’t really adhered to the unspoken laws. But usually, they got too many other things to do on a Saturday night and if you weren’t causing them too much of a problem they would leave you alone. Just monitoring, ask when you’re finishing, you know, just be fairly easy going about it. So there was times when they came in hard but generally you got away with. They didn’t use the Criminal Justice Bill that often in the city, funnily enough. So that made it a bit easier. But yeah, there’s different laws they could use – public nuisance laws, noise abatement things – so they could stop it any time they wanted to. There’s a lot more police activity now going on, they’re not so lenient about things as they were before.

Pearsall

There are a lot less empty spaces than there used to be, the city is more gentrified now.

Chris Liberator

Exactly! So yeah, that’s really how it worked, and why it was able to thrive for so long, and it’s become part of the culture of the city now. I mean, there’s a lot of news at the moment about illegal parties being shut down, there was a headline in the paper yesterday about 1000 illegal parties since lockdown in the capital, not acid techno, but just people setting up sound systems and doing parties. There’s definitely a new generation of people that are playing all sorts of music going out and doing parties because there’s no clubs or anything open so it’s gonna make the free party scene more vibrant.

We’ll see see how it develops, but for me you can’t kill the spirit.